No way Starcloud's putting a data centre in space in a Starship or $8.2 million

Abstract

Starcloud have claimed that a single 100-ton Starship launch could suffice to create a 40 MW space data centre (SDC) for $8.2 M. My analysis finds that this is infeasible in a single launch but requires a total of upto 22 launches. The SDC’s solar arrays require 4 launches determined by examining existing solar arrays on the ISS. Similarly, the ISS’s radiator benchmarks indicate that 13 launches would be needed for the SDC’s thermal management system. The server racks would require an addition 5 launches. I have not analysed the effects of MMOD/radiation shielding and the impact of propellant use for in-orbit assembly on launch numbers—this requires specifications and mission architectures that have not been made public and might not yet be fully developed. On the note of launch costs, the whitepaper’s (miscalculated) assumed launch cost is $30/kg. This makes their comparative economic analysis to terrestrial data centres unmoored from reality in the near term. Some experts speculate that $1000/kg would be an optimistic launch cost, which means $100M per launch and a total cost of $103.2M In 2021 dollars, a Falcon-9 launch costs $2600/kg and a Falcon Heavy’s at $1500/kg. So, even $500/kg is also a fairly optimistic estimate. . So, even if costs drop to $500/kg, a single launch results in an overall cost of $53.2M, not the purported $8.2M. If a second launch is needed, then the worst case number is $200M making it more than their reported cost of running a terrestrial data center (TDC).

Introduction

On Earth, data centres run on the existing electricity grid that, crudely put, use a combination of fossil fuels or terrestrial solar. Recently, technologists and entrepreneurs have talked up placing data centres in space to resolve three issues with terrestrial data centres (TDC):

- Data centres require tremendous amounts of energy, especially to run their cooling systems, which impacts the environment. TDCs already consume about 1-1.5% of global electricity and it’s safe to assume that this will only grow in the pursuit of AGI.

- A lot of waste heat is also generated running TDCs—so migrating to space would alleviate the toll on Earth’s thermal budget.

- Real estate for data centres is a massive bottleneck and this land could be used for other purposes. People are also generally annoyed by data centres coming up near their homes and you can’t expect everyone to want to relocate.

In space, 24/7 solar power is unhindered by day/night cycles, weather, and atmospheric losses, addressing the energy demands identified above. Now, Sam Altman has also talked up nuclear energy as a solution to point 1, which I suspect is probably more desirable than going into space but the regulatory barriers need to be resolved.

So, space, in theory, sounds like a panacea—as a space person, I’d love nothing more than for there to be a strong economic case for space1. But delivering a GW-scale SDC requires engineering solar arrays in the km scale, which will not be easy. Even the 40 MW system, that Starcloud used to benchmark against TDCs, needs a square of side 357 m. This would far exceed the span of the largest space structure ever built—the ISS is about 100 m in its longest dimension. As we’ll see there are other challenges with cooling.

A YCombinator-backed company, Starcloud Inc., released a whitepaper on this and I decided to dive in (with Claude to speedrun my analysis, of course). They begin by pointing us to some of the unique benefits of space solar, the main one being its 95%+ capacity factor versus just a median capacity factor of 24% for US terrestrial solar (under 10% in northern Europe). They continue to say that combined with 40% higher peak power due to no atmospheric losses, you get over 5x the energy output from the same solar array. This is not exactly my forte so I am not fact-checking these claims—let’s accept them as true.

My qualifications

If I can claim a bit of domain expertise, it’s on the space side. Reading Starcloud’s whitepaper, I felt I could use my limited expertise from designing mission for in-space assembled large space telescopes and analysing them to understand their techno-economic analysis.

Space challenges

Now, in-space assembly of large space structures, like large aperture telescopes, comes with its own challenges. For the sake of this analysis, I will classify them in the same three categories as I did at the start for TDCs but present them in reverse order:

- Real estate: Starcloud’s target is to achieve a 5 GW cluster, with solar arrays spanning 4 km by 4 km—this would comfortably become the largest structure in space yet—which will need launch followed by in-space assembly. This is analogous to TDC’s real estate.

- Cooling (aka Thermal Management): On Earth, data centres use air (convection) and water cooling (conduction) but in space, thermal management requires radiation, which is less efficient—convection is impossible in a vacuum and while water could extract heat from the center, cooling that heated up water would then pose another problem. That said, liquids are still needed for heat exchangers—this is covered later in context of the ISS.

- Finally, we could also think about if/when the carbon footprint of launches offset the benefits of a SDC. But the report suggests that achieving AGI could need 1 GW centres but large hyperscale Earth-based data centres today reach 100 megawatts (MW) meaning they “do not scale well or sustainably to gigawatt (GW) sizes”.

Now, I will treat that last item as speculative mostly because it is out of my wheelhouse. However, if it is true, then we will need some alternative (either nuclear or space-based data centres) but by examining the performance-driven launch numbers of the first two aspects (except in-space assembly in point 1), I imagine we will know how well the business case of this company adds up.

Starcloud’s Business Case

While one could begin by asking how much compute workload should be moved to space to make a meaningful dent from a climate angle—a really good reason to do so—economic incentives that guarantee large returns on investment are what appeal to private investors, at the end of the day. This is why Starcloud exists but space agencies haven’t invested in the area. So, this analysis begins by examining Starcloud’s numbers to justify their business case for SDC.

The whitepaper presents a table where the total costs of running a 40MW data centre cluster over ten years is determined to be $167M on Earth versus $8.2M for space; launch is the largest contributor to Starcloud’s total costs and they presume that one launch shall be enough, which I was skeptical about. As I show later, 300 of their benchmark Nvidia racks alone require 3 launches. That said, the whitepaper’s breakdown of costs for TDCs and SDCs are as follows:

Terrestrial:

- Energy: $140M (@ $0.04/kWh)

- Cooling: $7M (@ 5% of power usage)

- Water: 1.7M tons (@ 0.5L/kWh)

- Backup power: $20M

- Total: $167M

Space:

- Energy: $2M (cost of solar arrays)

- Launch: $5M (single launch)

- Radiation shielding: $1.2M

- Total: $8.2M

Now this means their projected energy cost is $0.002/kWh in space versus $0.045-0.17/kWh terrestrially—this is between 22 to 85 times cheaper. This raises questions about feasibility.

Estimating Launch Numbers

Launch costs are calculated from launch numbers, whose estimation requires some design specifications of the SDC (mass and geometry). As I read the whitepaper, it was unclear how SDC’s total mass would be 100 tonnes (or 167 tonnes) as these aren’t publicly shared—it is either proprietary information or yet to be defined. However, there are other ways to derive these design specs to verify the launch claims by using information in the whitepaper and filling in the gaps by examining state-of-the-art systems.

With these specs, a mass-based estimate of launches can be derived but one can also determine launch numbers that account for how the SDC’s elements fits into a rocket. Here, one essentially breaks the SDC into its subsystems to works out if/how their geometries fit into the volume of a launcher’s fairing. So, even if the mass estimates indicate the SDC fits into a single launcher, its volume might not necessarily be as accommodating.

The remainder of this blog is dedicated to estimating these launch numbers for three main part of the SDC: solar arrays, radiators, and servers.

Solar Arrays for SDC

Starcloud’s long-term goal is to build a 5 GW system, for which they require solar arrays spanning an area of 4km × 4km. This is a power density of 312 W/m² from which we can determine that their smaller 40 MW SDC needs 128,000 m² of solar panels. To pack this into a single Starship with a fairing volume of 1000 m³, we can determine the desired areal packing density which is the area of these arrays divided by the Starship’s fairing volume. This works out to 128 m²/m³.

\[\begin{align} {(Packing \, density)}_{desired} &=\frac{128,000}{1000}\\ &= 128 \, m^2/m^3 \end{align}\]This means that we would need to fit 128 m² of solar panels into a m³ of Starship where we have assumed that all of the paylod bay’s fairing volume is usable; but such packing efficiency is impractical but we will stick with this optimistic estimate for now. However, a more realistic estimate might permit about 80% of the available 1000 m³ to be used in which case the areal packing density is 160 m²/m³.

Next, I examine the performance of two space-proven designs for deployable solar arrays (of the three options that Starcloud propose to use as per their whitepaper). The first design is the Z-folds arrays which are the legacy design used on the ISS’s Solar Array Wings (SAW) and the second, called roll-out solar arrays (ROSA), augmented to the SAW’s and are set to become its next-generation replacements; this ISS variant is called iROSA.

Analysis of Solar Array Wings (SAW)

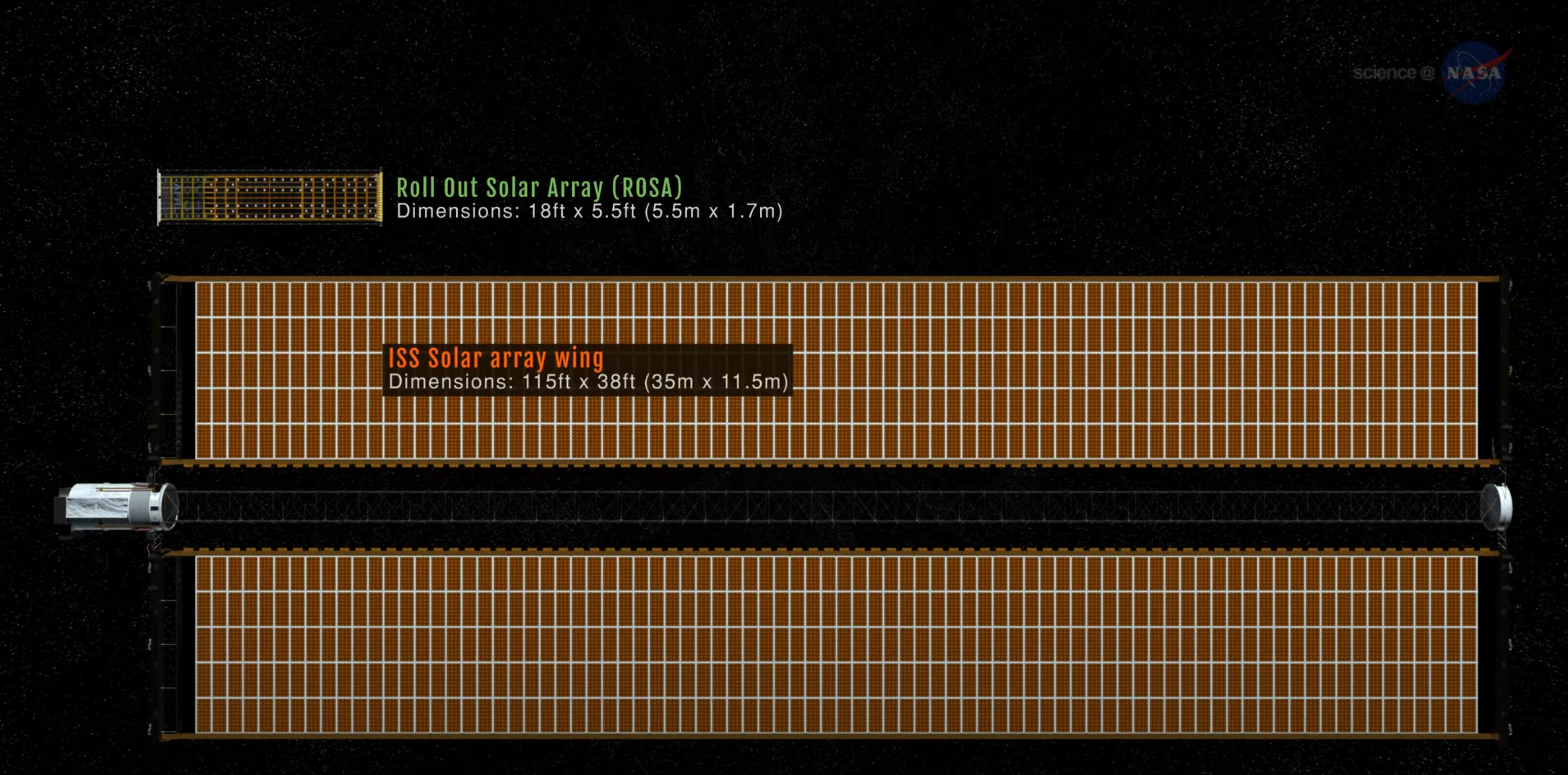

The image below shows one wing of the ISS Solar Array Win (SAW) and a small a Roll-Out Solar Array (ROSA).

The ISS has 8 such (SAWs) attached to trusses; four each on its port and starboard side—which explains why the truss names are prefixed with P’s and S’s (e.g., P-6 and S-6). Altogether, the eight solar array wings generate about 240 kilowatts in direct sunlight, or about 84 to 120 kilowatts average power (cycling between sunlight and shade).

Power Density

Each wing generates nearly 31 kilowatts (kW) of direct current power from two solar “blankets”. When fully extended, the pair span 35 metres in length and 12 metres in width. These are the largest ever deployed in space. The power density based on this wing span is 71.43 W/m² but a more appropriate estimate can be determined from the specs of the photovoltaic blanket. Each blanket comprises 16,400 cells of 8-cm by 8-cm; this gives the real actual light collecting area of each blanket and multiplying by two results in that for a single SAW.

So the power density of a wing with two blankets works out to 147.7 W/m² from:

\[\begin{align} {(Power \, Density)}_{SAW} &= \frac{Power}{Area} \\ &= \frac{31000W}{32800 \times .08^2} \\ &= 147.7 \, W/m^2 \end{align}\]So, achieving Starcloud’s assumed power density of 312 W/m² requires SAW technology to be 2.1x more efficient.

Volume-based launch numbers

The packing density of one SAW module (i.e., a pair of deployable blankets) can be determined from using its stowed volume within a launch vehicle. The data suggest that the module packs into a cuboid of square face of 4.57 m and 0.51 m thick—the result is a packing density of

\[\begin{align} {(Packing \, density)}_{SAW} &= \frac{35 \times 12}{4.57^2 \times 0.51}\\ &= 39.43 \, m^2/m^3 \end{align}\]This is far lower than the desired packing density desired by Starcloud to fit the solar arrays into a single Starship. The number of launches can thus be computed from the ratio of the Starcloud and SAW packing densities—a dimensionless number—which is 3.24.

\[N_{launches,volume} = \frac{128}{39.43} = 5 \text{ launches }\]This means we would need 4 launches using SAW technology. If we used the more realistic estimate packing density (160 m²/m³), it would need 5 launches.

Mass-based launch numbers

Each SAW wing has a documented mass of 1,100 kg and deploys 420 m² of active solar collection area (35 m × 12 m). This yields the mass density characteristic of the Z-fold SAW technology:

\[\begin{align} \rho_{mass,SAW} &= \frac{m_{SAW}}{A_{deployed,SAW}} \\ &= \frac{1100 \text{ kg}}{35 \times 12 \text{ m}^2} \\ &= \frac{1100 \text{ kg}}{420 \text{ m}^2} = 2.62 \text{ kg/m}^2 \end{align}\]This mass density reflects the integrated Z-fold system including photovoltaic cells, accordion deployment mechanisms, structural backing, electrical distribution networks, and mounting hardware designed for long-term space operations.

Applying this empirical mass density to Starcloud’s 128,000 m² solar array requirement:

\[\begin{align} m_{Starcloud,solar,SAW} &= A_{required} \times \rho_{mass,SAW} \\ &= 128,000 \text{ m}^2 \times 2.62 \text{ kg/m}^2 \\ &= 335,360 \text{ kg} = 335.4 \text{ tonnes} \end{align}\]Comparing mass-limited versus volume-limited launch requirements reveals a critical distinction from the iROSA case:

\[\begin{align} N_{launches,volume} &= 5 \text{ launches (from packing analysis)} \\ N_{launches,mass} &= \lceil \frac{335.4}{100} \rceil = 4 \text{ launches} \end{align}\]Analysis of ISS Roll-Out Solar Array (iROSA)

The ISS Roll Out Solar Arrays (iROSA) were launched in two pairs in June 2021 and November 2022 to augment to the first SAWs, launched in 2000 and 2006 and attached to the P6 and P4 Trusses. These SAWs were noticeably degrading towards the end of their 15-year life. Six of the intended 8 iROSAs have been added in following sequence:

- iROSA 1 and 2 was added in front of Old 4B and 2B solar arrays on P6 truss in June 2021;

- iROSA 3 and 4 was added in front of Old 3A and 4A solar arrays on S4 and P4 truss in December 2022;

- iROSA 5 was added in front of Old 1A solar array on S4 truss in June 2023; and

- and iROSA 6 was added in front of Old 1B solar array on S6 truss in June 2023. The seventh and eighth, are planned to be installed on the 2A and 3B power channels on the P4 and S6 truss segments in 2025.

Power Density

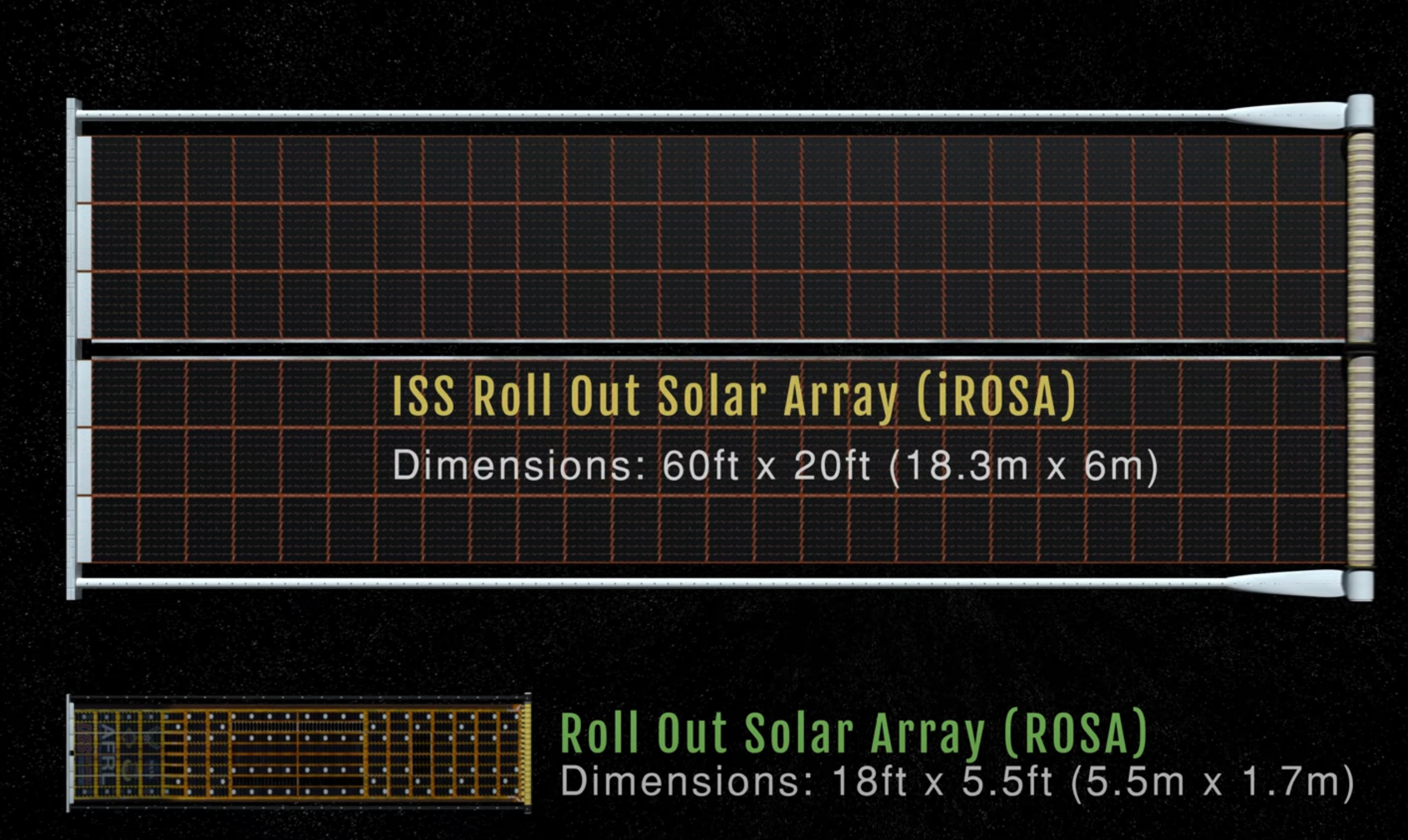

Each iROSA generates nearly 20 kilowatts (kW) of power from two rolled-up solar blankets. When fully extended, the pair span 18.3 metres in length and 6 metres in width. The gap between the blankets does not appear to be in the public domain but appears to be negligible than that between the pair of SAW blankets; the specifications of the solar cells and their arrangement are also not known.

So, the power density here is based purely on the wing span, which works out to about 182.1 W/m² from:

\[\begin{align} {(Power \, Density)}_{iROSA} &= \frac{Power}{Area}\\ &= \frac{20000}{18.3 \times 6}\\ &= 182.1 \, W/m^2 \end{align}\]So, to achieve Starcloud’s assumed power density of 312 W/m², their solar technology would need to be 1.71x more efficient than iROSA.

Volume-based launch numbers

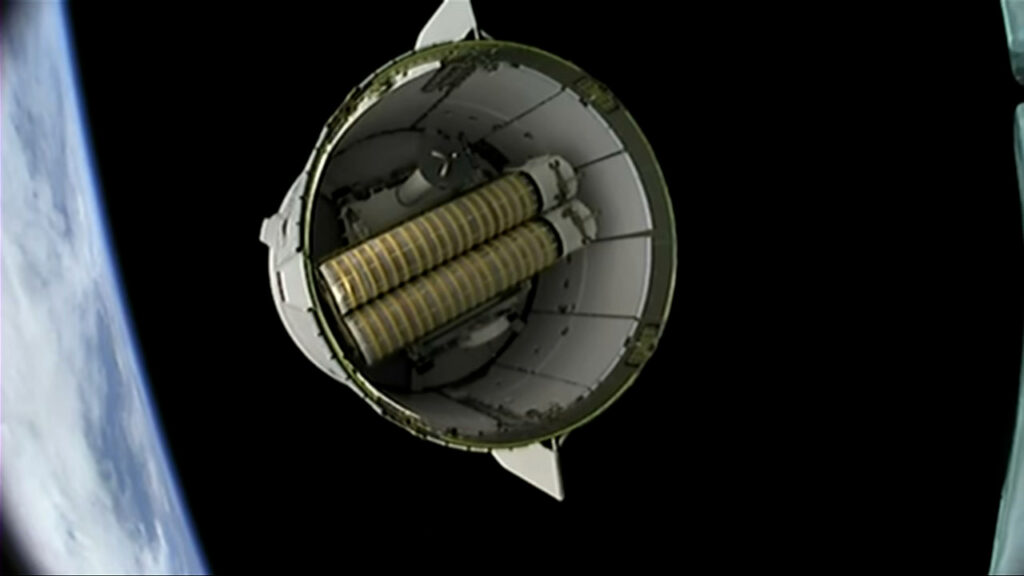

iROSA canisters stowed in cargo Dragon’s trunk. Source

As done with the SAW module analysis (i.e., a pair of deployable blankets), we can use the stowed volume of an iROSA module to compute the number of launches. Sadly, this data is also not public but estimates can be made by examining its imagers stowed in a cargo Dragon as well as alongside humans for scale. The iROSAs packed into a cargo Dragon trunk and each blanket packed into a canister; the length of this canister is assumed to be 3 m, a dimension that remains unchanged for either blanket as it rolls out. Each blanket’s 18.3 m deployed span can be assumed to pack into a canister of diameter of 0.3 m. So two such canisters per iROSA leads to a packing density of

\[\begin{align} {(Packing \, Density)}_{iROSA} &= \frac{18.3 \times 6}{2\pi \times 0.15^2 \times 3} \\&= 258.78 \, m^2/m^3 \end{align}\]Again, one can determine the number of launches for the SDC’s solar panels by computing the ratio of the desired and iROSA packing densities. At 0.49, this is well under a single Starship launch.

Mass-based launch numbers

While the packing density analysis suggested favorable volumetric efficiency for iROSA technology, the mass constraint presents a secondary limitation that requires careful examination. Each iROSA unit has a documented mass of 340 kg and deploys 109.8 m² of active solar collection area yielding a mass density for modern roll-out solar technology:

\[\begin{align} \rho_{mass,iROSA} &= \frac{m_{iROSA}}{A_{deployed,iROSA}} \\ &= \frac{340 \text{ kg}}{18.3 \times 6 \text{ m}^2} \\ &= \frac{340 \text{ kg}}{109.8 \text{ m}^2} = 3.10 \text{ kg/m}^2 \end{align}\]This mass density reflects the integrated system including photovoltaic cells, deployment mechanisms, structural backing, electrical harnesses, and mounting hardware required for autonomous space deployment. Scaling this empirical mass density to Starcloud’s 128,000 m² solar array requirement reveals the magnitude of the mass challenge for their power generation system:

\[\begin{align} m_{Starcloud,solar} &= A_{required} \times \rho_{mass,iROSA} \\ &= 128,000 \text{ m}^2 \times 3.10 \text{ kg/m}^2 \\ &= 396,800 \text{ kg} = 396.8 \text{ tonnes} \end{align}\]Comparing the mass-limited and volume-limited launch requirements reveals the constraining factor for solar array deployment:

\[\begin{align} N_{launches,volume} &= \frac{V_{required}}{V_{Starship}} = \frac{494.6}{1000} \approx 1 \text{ launch} \\ N_{launches,mass} &= \lceil \frac{m_{Starcloud,solar}}{m_{Starship,payload}} \rceil \\ &= \lceil \frac{396.8}{100} \rceil = 4 \text{ launches} \end{align}\]The analysis reveals that mass emerges as the limiting constraint for solar array deployment, requiring 3 launches compared to the single launch suggested by volumetric analysis alone. This represents a 3× penalty where mass considerations override the favorable packing density characteristics of roll-out solar technology.

The comparison between SAW and iROSA mass densities reveals important technological evolution patterns:

- SAW Z-fold: 2.62 kg/m² (more mass-efficient)

- iROSA roll-out: 3.10 kg/m² (18% heavier per unit area)

Despite being newer technology, iROSA exhibits higher mass density due to the robust deployment mechanisms required for roll-out architecture. However, iROSA’s superior volumetric packing efficiency (258.78 vs 39.43 m²/m³) more than compensates for this mass penalty, resulting in overall lower launch requirements.

Summary of Launch Costs for Solar Panels

Our calculations thus far are summarised below, where the pessimistic launch cost is based on a $100M Starship launch and an optimistic cost uses Starcloud’s $5M launch cost assumption:

Mass constraints dominate solar array deployment requirements

| Array Design | Launches | Optimistic cost ($) | Pessimisitic cost ($) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Z-fold | 5 | 25M | 500M |

| Roll-out | 4 | 20M | 400M |

The iROSA analysis reveals that mass, not volume, constrains solar array deployment—requiring 3 launches despite favorable packing density. This pattern emerges consistently across both power generation and thermal management systems, where mass penalties systematically exceed volumetric limitations for large-scale space infrastructure.

So this begs the question if on what the launch estimates for the radiators look like.

Radiators for SDC

Since space lacks convective and conductive heat transfer, all waste heat must be radiated cooling to reject the full 40 MW thermal load generated by the data center. This is typically done via deployable surfaces. Starcloud propose a radiator system operating near 20 °C. Its theoretical limit is governed by the Stefan–Boltzmann Law, which tells us that

\[P_{\text{body}} = \varepsilon \cdot \sigma \cdot T^4\]where, emissivity for a black body, \(\varepsilon = 1\); the Stefan-Boltzmann constant is \(\sigma=5.67 \times 10^{-8} \, \text{W}\text{m}^{−2}\text{K}^{−4}\); and radiator temperature is \(T = 293.15\,\text{K}\) so we can determine that the heat radiated from both sides of a \(1 \, \text{m}^2\) plate is

\[P_{\text{radiator}} = 2 \, P_{\text{body}}= 770.48\,\text{W}\]So, with practical adjustments for real materials and environmental exposure, the net heat radiated by the plate also depends on the heat absorbed from the Sun \((P_{\text{Sun}})\) and Earth \((P_{\text{Earth}})\).

The net heat radiated is then:

\[P_{\text{net}} = P_{\text{radiator}} - (P_{\text{Sun}} + P_{\text{Earth}})\]One side of the radiator is in direct sunlight so the heat it absorbs is calculated as:

\[\begin{align} P_{\text{Sun}} &= (\alpha \cdot S) \\ &= 0.09 \cdot 1366 \\ &= 122.94 , \text{W/m}^2 \end{align}\], where the plate’s absorptivity is \(\alpha = 0.09\), and solar irradiance in space is \(S = 1366 \text{W}/\text{m}^2\). The thermal energy absorbed by the plate from the Earth’s albedo and blackbody radiation, is determined from:

\[\begin{align} P_{\text{Earth}} &= \alpha \cdot F \cdot (Al \cdot S + \sigma \cdot T_{\text{earth}}^4) \\ %% %%&= 0.09 \cdot 0.25 \cdot (0.3 \cdot 1366 + 5.67 \times 10^{-8} \cdot (273.15 - 20)^4) \\ &= 14.46 \,\text{W/m}^2 \end{align}\]where, we have some additional terms such as the view factor \((F = 0.25)\); Earth’s black body temperature \((T_{Earth} = -20 °C)\); and Earth’s albedo \((Al = 0.3)\).

Thus, the net radiative power per square meter of a passive radiator system operating near 20 °C is therefore:

\[\begin{align} P_{\text{rad, net}} &= \underbrace{770.48}_{\text{Radiated (both sides)}} - \underbrace{122.94}_{\text{Sun absorbed}} - \underbrace{14.46}_{\text{Earth absorbed}}\\ &= \boxed{633.08\,\text{W/m}^2} \end{align}\]However, this theoretical calculation assumes heat is uniformly distributed across the radiator surface. The real engineering challenge is getting heat from the source (in this case, the data center) to every point on the radiator surface without adding prohibitive mass in pumps, pipes, and manifolds—similar to how your home radiator needs internal channels to distribute hot water throughout the unit.

Radiator Area Required for the SDC

This can be used to compute the area needed to radiate 40 MW of waste heat (assuming as much heat is generated as electricity is produced):

\[A_{\text{rad}} = \frac{40{,}000{,}000}{633.08} \approx \boxed{63{,}183.1\,\text{m}^2}\]This amounts to approximately 0.063 km² of radiator surface area, which their whitepaper also claims must fit within the same Starship fairing volume of 1,000 m³. While this is clearly impossible—given that the solar arrays alone already require five separate launches—we can calculate the required areal packing density for the radiator to fit inside a single Starship. It would need to achieve an areal packing density of 63.18 m²/m³, an extraordinarily high (and likely unachievable) figure.

\[\begin{align} {(Packing \, density)}_{desired} &=\frac{63{,}183}{1000}\\ &= 63{.}18 \, m^2/m^3 \end{align}\]Again, as was the case with the solar arrays, a more realistic estimate would be based on 80% of the fairing volume being usable which would lead to 79 m²/m³ as the areal packing density.

The ratio of solar to radiator areas is then:

\[\frac{A_{\text{solar}}}{A_{\text{rad}}} = \frac{128{,}000}{63{,}183} \approx 2.02\]which clarifies Starcloud’s statement that the radiator area needed is indeed roughly half that of the solar array. However, examining the power density ratio of the radiator to solar arrays tells us that the performance of the radiator is just about twice better than the power generation capacity of the solar panels.

For an idealized two-sided blackbody plate’s power density, this ratio is 2.68; this is closer to the paper’s statement of “roughly three times the electricity generated per square meter by solar panels”. Thus, it is important to clarify that under Starcloud’s assumed radiator and environmental parameters, the whitepaper’s commentary could be strengthened by focusing on a radiator system’s heat rejection capability being approximately twice, not three times, the power per square meter as the solar array generates electricity. To ground this theoretical model in real-world hardware, we now compare it against the ISS’s proven radiator systems.

The ISS systems as a benchmark

The ISS’s systems and experiments consume a large amount of electrical power, almost all of which is converted to heat.. So, ~120 kW of electrical power essentially all of which becomes waste heat that must be radiated away. Its radiators operate at -40°C—much colder than Starcloud’s assumed 20°C. Keeping same emissivity as the Starcloud system (\(\epsilon=0.92\)), we can determine that the heat to be radiated per unit area as \(P_\text{ISS} = 308.7\,\text{W/m²}\) and the net heat radiated, after accounting for environmental effects, is \((P_{\text{ISS}})_\text{net} = 171.3\,\text{W/m²}\). To achieve thermal control and maintain components at acceptable temperatures, this heat requires radiators with an area of

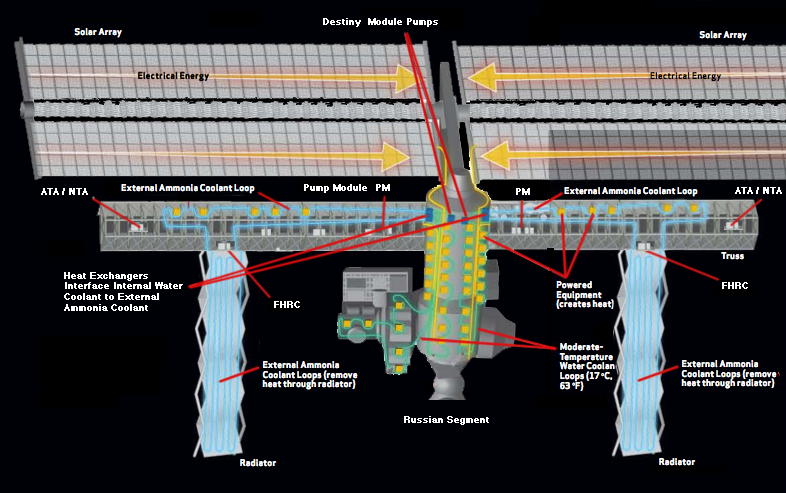

\[A_{\text{required}} = 120,000/171.3 W/m² = 700\,\text{m²}\]For this purpose the ISS makes use of two systems. The Active Thermal Control System (ATCS) handles heat rejection when the combination of the ISS external environment and the generated heat loads exceed the capabilities of the Passive Thermal Control System (PTCS). The PTCS is made of external surface materials, insulation such as MLI, and heat pipes. The ATCS Overview comprise equipment that provide thermal conditioning via fluid flow, e.g. ammonia and water, and includes pumps, radiators, heat exchangers, tanks, and cold plates.

The ATCS mechanically pumps fluid in closed-loop circuits to perform three tasks: collect heat, transport heat, and reject heat. Waste heat can be removed via two structures—cold plates and heat exchangers—both cooled by a circulating ammonia loops on the outside of the station. The heated ammonia circulates through large radiators located on the exterior of the Space Station, releasing the heat by radiation to space that cools the ammonia as it flows through the radiators.

From a practical standpoint, the ATCS radiates heat generated by two sources—from the solar arrays and from inside the ISS modules. The Photovoltaic Thermal Control System (PVTCS) handles the former whereas the latter heat is radiated by the Internal Active Thermal Control System (IATCS) and External Active Thermal Control System (EATCS). They are discussed further below:

EATCS (External Active Thermal Control System) Radiators

The EATCS consists of an internal, non-toxic, water coolant loop used to cool and dehumidify the atmosphere—this is the Internal Active Thermal Control System (IATCS). It transfers collected excess heat from electronic and experiment equipment and distributes it to the Interface Heat Exchangers. From these heat exchangers, ammonia is pumped into external radiators—the External Active Thermal Control System (EATCS)—that emit heat as infrared radiation and this ammonia cycles back to the station. In this way, the EATCS cools the US modules, Kibō, Columbus, and also the main power distribution electronics of the S0, S1 and P1 trusses. It can reject up to 70 kW, which is more than the 14 kW of the Early EATCS (or EEATCS).

PVTCS (Photovoltaic Thermal Control System) Radiators

The Photovoltaic Thermal Control System (PVTCS) consists of ammonia loops that collect excess heat from the Electrical Power System (EPS) components in the Integrated Equipment Assembly (IEA) on P4 and eventually S4 and transport this heat to the PV radiators (located on P4, P6, S4 and S6) where it is rejected to space. The PVTCS consist of ammonia coolant, eleven coldplates, two Pump Flow Control Subassemblies (PFCS) and one Photovoltaic Radiator (PVR).

Sizing of ISS Radiators

- EATCS: Page 3-16 of ISS Handbook confirms that there are 6 radiator ORUs (3 on S1 truss, 3 on P1 truss). Page 14 of ATCS Overview, each ORU weighs 1,122 kg and spans 23.3 m × 3.4 m (i.e., 79.2 m²) for a total EATCS area of 475 m² from six ORUs. The 6 radiators are capable of radiating 70 kW of heat with a specific heat rejection of 11.1 W/kg.

- PVTCS: PVTCS: The ATCS Overview specifies 4 Photovoltaic Radiators (PVRs), one per solar truss (S4, P4, P6, S6). Each PVR weighs 741 kg and spans 3.12 m × 13.6 m (i.e., 42.4 m²) for a total PVTCS area of 170 m² from four PVRs. The 4 radiators are capable of radiating 56 kW of heat with a specific heat rejection of 18.9 W/kg.

-

Combined Radiator Performance Combined area: Their combined area is 645 m², which is quite close to our theoretical estimate above for the ISS using the Stefan-Boltzmann law. Together they reject about 126 kW of heat, which is also close to the power generated by the ISS. Then we can measure they performance per unit area by dividing heat radiated by area to get 195 W/m². We can also calculate the specific heat rejection by dividing dividing heat radiated by mass to get 195 W/kg with a combined specific heat rejection of 13.5 W/kg.

Mass-based launch numbers

The ISS thermal control systems provide empirical mass data for space-qualified radiator technology. Each system exhibits distinct mass characteristics reflecting their different operational requirements and design constraints.

EATCS Radiator: The EATCS comprises 6 Orbital Replacement Units, each of which has a documented mass of 1,122 kg and deploys 79.2 m² of radiating surface. This yields a mass density of:

\[\begin{align} \rho_{mass,ORU} &= \frac{m_{ORU}}{A_{deployed,ORU}} \\ &= \frac{1122 \text{ kg}}{79.2 \text{ m}^2} = 14.16 \text{ kg/m}^2 \end{align}\]PVTCS Radiator (PVR): The Photovoltaic Thermal Control System comprise 4 radiator panels, being smaller and serving dedicated solar array cooling, exhibit higher mass density. Each PVR unit masses 741 kg across 42.4 m² of radiator surface area:

\[\begin{align} \rho_{mass,PVR} &= \frac{m_{PVR}}{A_{deployed,PVR}} \\ &= \frac{741 \text{ kg}}{42.4 \text{ m}^2} = 17.48 \text{ kg/m}^2 \end{align}\]These mass figures (14-17 kg/m²) reflect not just the radiating surface, but the complex internal heat distribution networks. Each radiator contains ammonia coolant loops, manifolds to distribute flow, internal channels to reach every corner of the panel, pumps, and mounting hardware. This internal ‘plumbing’ represents the majority of the radiator mass—the actual radiating surface is relatively lightweight.

Combined Systems Mass Performance: The complete ISS thermal control system comprises the PVTCS units and ATCS, yielding a system-level mass density of:

\[\begin{align} m_{ISS,total} &= 4 \times 741 + 6 \times 1122 = 9696 \text{ kg} \\ \rho_{mass,ISS} &= \frac{9696}{645} = 15.03 \text{ kg/m}^2 \end{align}\]The radiator mass challenge stems from the need to transport heat internally within each panel. Unlike solar arrays that only need electrical connections, radiators require heavy fluid distribution systems to ensure uniform temperature across their entire surface. This internal heat transport infrastructure—not the radiation physics itself—drives the 4-5x mass penalty compared to solar panels.

Scaling these empirical mass densities to Starcloud’s 63,190 m² radiator requirement reveals the magnitude of the mass challenge:

\[\begin{align} m_{Starcloud,ORU} &= 63190 \times 14.16 = 894.9 \text{ tonnes} \\ m_{Starcloud,PVR} &= 63190 \times 17.48 = 1103.4 \text{ tonnes} \\ m_{Starcloud,ISS} &= 63190 \times 15.03 = 949.8 \text{ tonnes} \end{align}\]With Starship’s 100-tonne payload capacity to LEO, the mass-limited launch requirements become:

\[\begin{align} N_{launches,ORU} &= \lceil \frac{894.9}{100} \rceil = 9 \text{ launches} \\ N_{launches,PVR} &= \lceil \frac{1103.4}{100} \rceil = 12 \text{ launches} \\ N_{launches,ISS} &= \lceil \frac{949.8}{100} \rceil = 10 \text{ launches} \end{align}\]Our radiator mass analysis reveals the fundamental constraint limiting Starcloud’s single-launch architecture. The calculations are summarised below, where the pessimistic launch cost is based on a $100M Starship launch and an optimistic cost uses Starcloud’s $5M launch cost assumption:

ISS radiators launch manifest based on mass estimates.

| Radiator Technology | Launches | Optimistic Cost ($) | Pessimistic Cost ($) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EATCS (ORU) | 9 | 45M | 900M |

| PVTCS (PVR) | 12 | 60M | 1.2B |

| ISS Combined | 10 | 50M | 1B |

The challenge of launching radiators for a 40 MW SDC requires at least 9 launches if we are building on ISS technology. This also shows that the solar array mass density of 3.10 kg/m² proves remarkably efficient compared to radiator systems (14-17 kg/m²), reflecting the fundamental difference between power generation and thermal management technologies. Solar arrays primarily consist of thin photovoltaic films with minimal structural requirements, while radiators demand substantial mass for heat transfer fluids, thermal exchange surfaces, and robust mounting systems. The radiator mass suggests that revolutionary advances in thermal management technology—achieving 90% mass reduction relative to ISS systems—would be necessary to approach single-launch viability. Such improvements exceed materials advances and represent unprecedented engineering breakthroughs for space-qualified thermal control systems.

Volume-based launch numbers

The radiator packing density calculation requires careful consideration of how panels fold and stack when stowed. For the ISS radiator systems, we can model the folding geometry as follows. Each radiator unit consists of multiple panels that fold accordion-style along their longest dimension. When stowed, these panels stack atop one another, creating a total thickness equal to the number of panels multiplied by individual panel thickness. Unlike the previous analysis on solar panels where a fixed 0.51 m thickness for the stowed volume was inherited from solar panel empirical data, radiator panels are not as well documented publicly. We examine each of the radiator designs below:

EATCS Radiator (ORU) Analysis: The External Active Thermal Control System radiator deploys as a 23.3 m × 3.4 m array with 8 panels folding along the 23.3 m dimension:

\[\begin{align} W_{stowed} &= W_{deployed} = 3.4 \text{ m} \\ L_{stowed} &= \frac{L_{deployed}}{N_{panels}} = \frac{23.3}{8} = 2.91 \text{ m} \\ T_{stowed} &= N_{panels} \times t_{panel} = 8 \times 0.2 = 1.6 \text{ m} \end{align}\] \[\begin{align} V_{ORU} &= 3.4 \times 2.91 \times 1.6 = 15.84 \text{ m}^3 \\ \rho_{ORU} &= \frac{79.2}{15.84} = 5 \text{ m}^2/\text{m}^3 \end{align}\]PVTCS Radiator (PVR) Analysis: The Photovoltaic Thermal Control System radiator deploys as a 3.12 m × 13.6 m array consisting of 7 individual panels. When folded, each panel maintains its 3.12 m width but reduces its length to 13.6/7 = 1.94 m. Assuming each panel has a thickness of 0.2 m, the stowed configuration becomes:

\[\begin{align} W_{stowed} &= W_{deployed} = 3.12 \text{ m} \\ L_{stowed} &= \frac{L_{deployed}}{N_{panels}} = \frac{13.6}{7} = 1.94 \text{ m} \\ T_{stowed} &= N_{panels} \times t_{panel} = 7 \times 0.2 = 1.4 \text{ m} \end{align}\]The stowed volume and packing density for a single PVR unit are:

\[\begin{align} V_{PVR} &= W_{stowed} \times L_{stowed} \times T_{stowed} \\ &= 3.12 \times 1.94 \times 1.4 = 8.47 \text{ m}^3 \\ \rho_{PVR} &= \frac{A_{deployed}}{V_{stowed}} = \frac{42.4}{8.47} = 5 \text{ m}^2/\text{m}^3 \end{align}\]Combined ISS Performance: So for their combined performance on the the ISS, we account for the 6 ORU radiators of the EATCS and 4 radiators of the PVTCS to yield:

\[\begin{align} V_{ISS,total} &= 4 \times V_{PVR} + 6 \times V_{ORU} \\ &= 4 \times 8.47 + 6 \times 15.84 = 128.9 \text{ m}^3 \\ \rho_{ISS,combined} &= \frac{645}{128.9} = 5.00 \text{ m}^2/\text{m}^3 \end{align}\]Despite variations in their deployed areas, these radiator systems have the same packing densities. The number of launches is then computed as 13 from the ratio of Starcloud’s desired packing density to the ISS benchmarks above

\[N_{launches} = \lceil \frac{63.18}{5} \rceil = 13 \text{ launches}\]The volume-based launches (13) and mass-based launches (9-12) are quite similar despite the math demonstrating that volume emerges as the dominant constraint for large-scale radiator deployment. This reflects the fundamental physics of thermal management systems, which require substantial structural mass (for heat transfer fluids, manifolds, mounting hardware, and thermal exchange surfaces) that also pack less efficiently than the roll-out solar arrays. Recalling that 63.18 m²/m³ is assuming all of the payload bay is accessible—more realistically this could be 79 m²/m³, which means this could be up to 16 launches.

While this analysis demonstrates that volume, not mass, is the critical limiting factor for large-scale radiator deployment, it should be noted that this is dependent on the assumed panel thickness panel of 0.2 m. Reducing panel thickness to 0.05 m reduces volume-defined launches to 4 but then we fall back to radiator mass being the critical limiting factor so we will still need between 9-12 launches when using ISS-like technology. This transforms the claimed $5M single-launch deployment into a $1B+ multi-launch operation using realistic launch costs and flight-proven thermal management technology. Achieving single-launch feasibility requires a packing density of 63.18 m²/m³—roughly an order of magnitude beyond demonstrated deployable radiator technologies.

Thin-film thermal management, similar to the iROSA, are currently in early stage research phase for cooling solar panels for space-based solar power but how, if at all, this can also be applied to chips is unclear to me Current concept paper on this technology. . Liquid cooling technologies with heat pipes and heat exchangers will still be needed, which will almost always be quite bulky. With this, we close our discussion with an examination of server racks.

Server Racks

Having established that radiators are more dominant than power systems on the SDC launch manifest, it is also worth deriving the SDC’s implicit server mass assumptions and compare them to industry benchmarks. Their total compute deployment of ~40 MW is to be achieved using 300 Nvidia GB200 NVL72 racks with each rack needing 120 kW per rack. This is claimed to take up 50% of Starship’s payload bay volume. First, I clarify that the calculations align with the actual specs of the rack:

\[\begin{align} P_{effective,per-rack} &= \frac{P_{total}}{N_{racks}} \\ &= \frac{40{,}000 \text{ kW}}{300} \\ &= 133.3 \text{ kW per rack} \end{align}\]This is closer to the stated power needs of 132 kW per rack. The rack apparently weighs 1.36 metric tonnes. So, for 300 racks we have:

\[\begin{align} m_{servers,Starcloud} &= N_{racks} \times m_{rack} \\ &= 300 \times 1{,}360 \text{ kg} \\ &= \boxed{408 \text{ tonnes}} \end{align}\]These will require 5 Starship launches: \(N_{launches,servers} = \lceil \frac{408}{100} \rceil = 5 \text{ launches}\)

The racks alone are over a single Starship launch.

Conclusion

So after this analysis, the launch profile looks like this:

Mass constraints dominate solar array deployment requirements

| Component | Mass (tonnes) | Launches | Optimistic Cost ($M) | Pessimistic Cost ($B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Servers | 408.0 | 4-5 | 20-25 | .4-.5 |

| Solar Arrays | 396.8 | 4-5 | 20-25 | .4-.5 |

| Radiators | 894.9-1103.4 | 9-16 | 45-80 | .9-1.6 |

| Total System | 1,686.6 | 17-22 | 85-130 | 1.7-2.2 |

Even using Starcloud’s own optimistic specifications, the support infrastructure still outweighs servers by nearly 4 times, requiring upto 22 total launches versus their claimed single launch—representing a 2,200% cost increase from $5M to $110M using an optimistic launch cost ($5M/launch), or $2.2B using a pessimistic $100M/launch ($100M/launch). While there is more one could analyse, the analysis demonstrates that regardless of server mass assumptions—commercial rack deployment (300 tonnes) or with optimized space hardware (maybe 150 tonnes?)—the fundamental constraint remains thermal management volume, which systematically dominates launch requirements for large-scale space-based computing systems. This work is not to say that SDCs have no value but that the case for SDC needs more realistic techno-economic analysis.

Further Reading

- Pete Lynn makes the case for SDCs here and here.

- BBC article The plans to put data centres in orbit and on the Moon

- MIT Technology Review article Should we be moving data centers to space?

- Review of advanced radiator technologies for spacecraft power systems and space thermal control

- International Space Station Evolution Data Book Volume I. Baseline Design Revision A Catherine A. Jorgensen, Editor FDC/NYMA, Hampton, Virginia

- Active Thermal Control System (ATCS) Overview

- MANAGING RISK FOR THERMAL VACUUM TESTING OF THE INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION RADIATORS

- Black Body Radiation

-

As a space aficionado, my only gripe with SDC is that it adds to the data services space economy, which we know is proven to work well with GPS and satellite communications, but does little to advance the scale of human habitation in orbit. ↩