Where is my von Braun wheel?

In 1962. There — that answers the clickbaity title right away.

NASA had viable designs for rotating wheel space stations that could have given astronauts artificial gravity. Then, the Apollo program effectively killed them.

While NASA’s lunar focus delivered the historic moonshot, it dismantled a promising engineering effort at Langley Research Center that might have revolutionized human spaceflight. That decision set us on a half-century trajectory of small, zero-gravity stations that continue to plague astronauts with muscle atrophy, bone loss, and vision problems.

Had NASA maintained its parallel pursuit of artificial gravity, we might now have permanent orbital settlements supporting deep space missions rather than the limited outposts we’ve settled for. This historical pivot point matters today as commercial space companies contemplate artificial gravity again, potentially correcting a costly detour in humanity’s path to becoming a spacefaring civilisation.

The need for artificial gravity

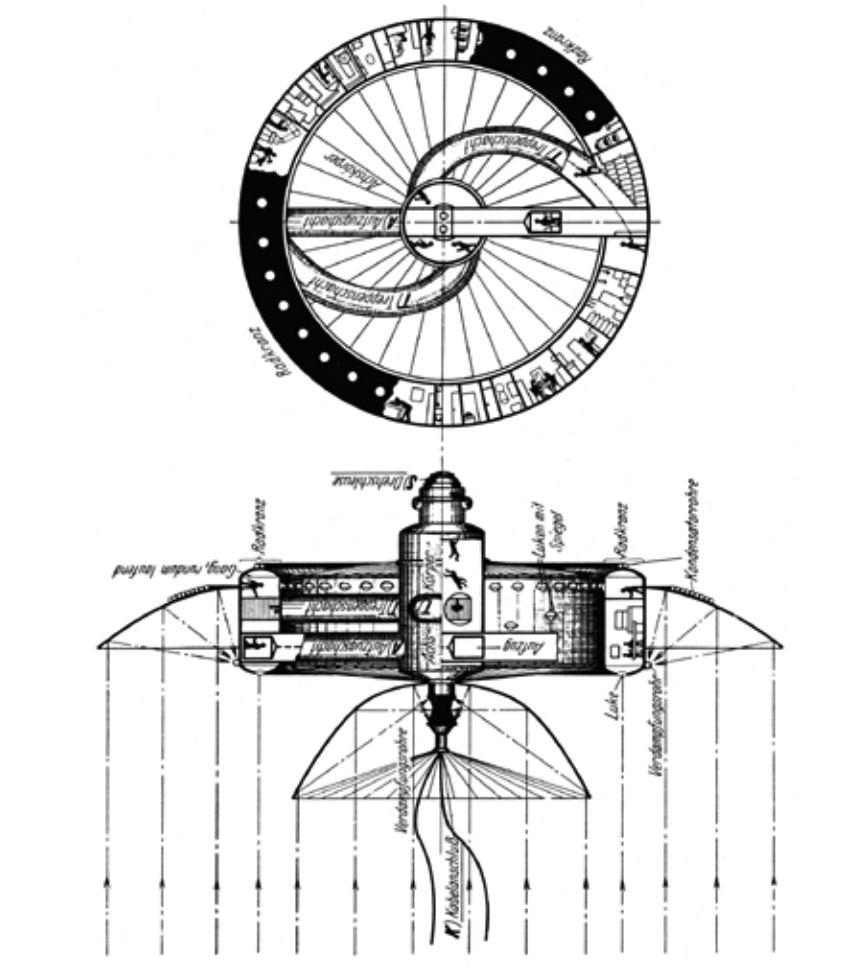

Early space visionaries, such as Werner von Braun, strongly believed that settling the solar system required developing technologies to generate artificial gravity within orbiting habitats as — rephrasing Heinlein — space is a harsh mistress. Modern-day astronauts exercise a few hours each day to overcome microgravity’s effects on the body. Von Braun was convinced that rotating wheel space stations prevented such physiological problems and were thus “as inevitable as the rising sun”. In these systems, humans live along the periphery of a wheel, within which they experience gravity due to the wheel’s rotation. Popularised by von Braun in his 1949 sci-fi novel, Project Mars, and the 1956 Disney piece, the concept actually traces back to Herman Potočnik’s 1929 book The Problem of Space Travel. Its legacy is perhaps why many felt that an operational spinning station was, at best, a couple decades away.

The difficulty of building large stations

Rotational forces applied to wine tasting.

This elegant solution to generate artificial gravity, however, comes with a major engineering challenge. Much like a ferris wheel, the wheel’s rotation could disorient astronauts if spun too fast. If the wheel spins slowly then its physics dictates it must be quite large. For example, one of von Braun’s designs called for a massive 75 metre diameter wheel that generated lunar gravity if spun at 3 rpm and Earth-like gravity at 5 rpm — this range is considered reasonable for astronauts.

However, the physics of rockets presents a different obstacle as it must be slender, like an arrow, to escape Earth’s gravity well and reach orbit. This defines the main upstream engineering challenge: how can we fit enormous space structures into slender rockets? For context, even Starship’s upper-stage, which is about 9 metres wide and 22 metres tall cannot fit von Braun’s conceptual station in a straightforward manner.

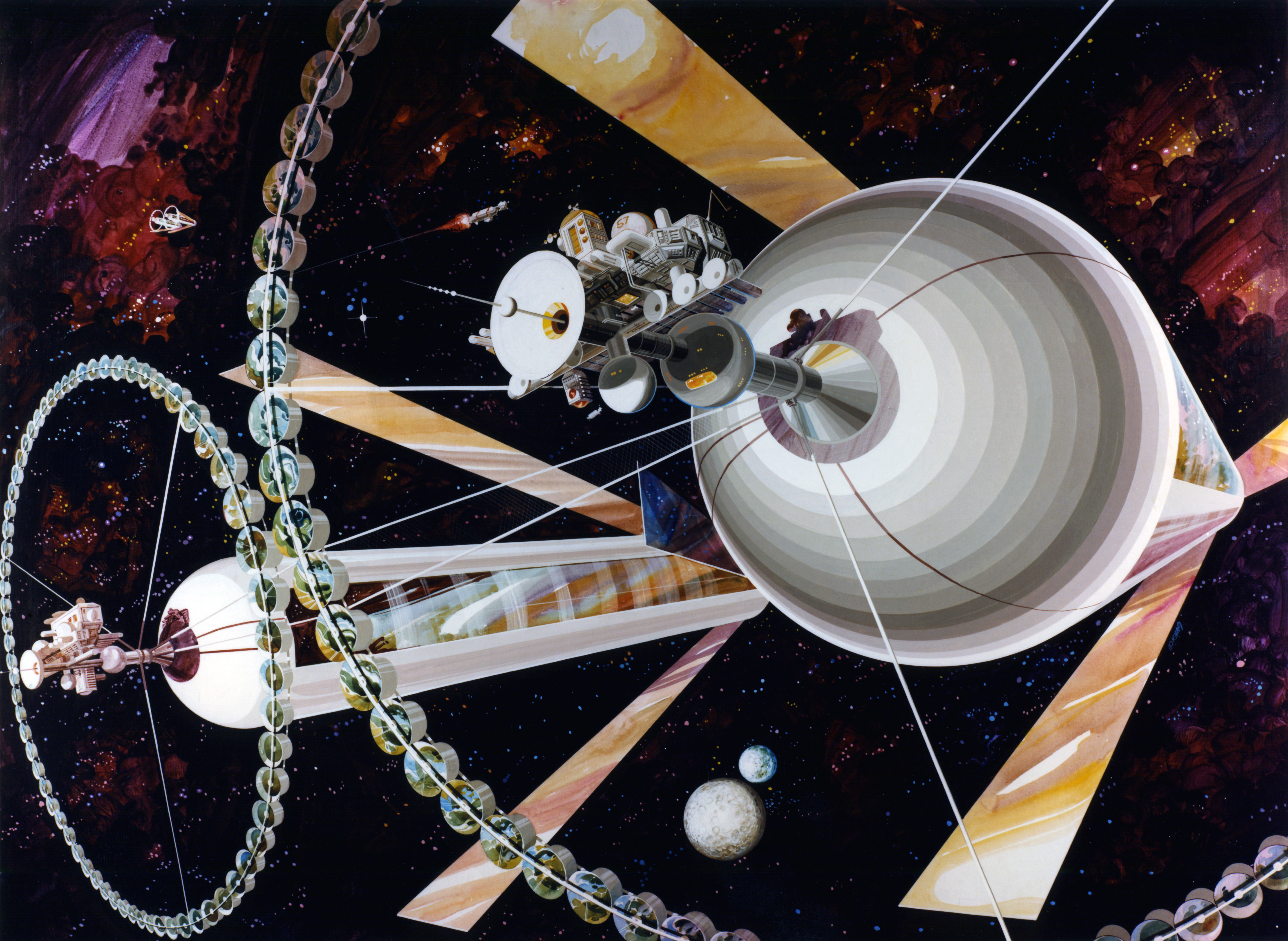

Architects of the International Space Station (ISS), the largest space structure ever built, tackled a similar packing problem using multiple smaller spacecraft which connect, like space Ikea, into a structure greater than its parts. Such in-space assembly involves spacecraft either gently crashing into each other at specific connection points (a manoeuvre called rendezvous and docking) as well as astronauts and space cranes supporting finer assembly tasks. While this works great in theory, the ISS’s assembly needed over 40 rocket launches spanning several years (and even more launches for cargo resupply and repairs). More damning is the typical ISS crew size of 7, which is a little over twice that of the first ever space station, Salyut, from 1972. Clearly 50 years of space station development does not indicate that such modular in-orbit assembly will scale to von Braun’s anticipated 80 humans or, more relevant today, Starship’s 100 any time soon. Civilisation-scale megastructures like the Stanford Torus and O’Neill cylinders appear even more outlandish to discuss today than when they were first proposed in the 70s.

From this vantage point, it is quite clear that the architectural bottleneck is a technology running through all operational space stations so far: their use of small ‘tin can’ modular spacecraft as the centrepiece for assembly, which is a legacy of Apollo. This, in my opinion, is unfit for building large space stations at scale or speed. But how did we get here? To understand this, we need to look into the pre-Apollo era space technology development programs and the consequence of Apollo’s announcement on them.

A pre-Apollo solution: unitised stations

From 1959 till 1962, NASA Langley explored various architectures to accelerate towards von Braun’s vision. A former Director of Aeronautical Research at NASA Langley, Larry Loftin, saw these stations as essential to crewed exploration of our Moon and planets following the success of Project Mercury. In keeping with this, he instigated a conference in 1959 to explore ideas at Langley, two of which were taken to the prototype stage. These early concepts are notable not only for their ambition in directly pursuing von Braun’s vision but also for what now feels like a very counterintuitive way of realising large stations as “unitised” structures i.e., a single structure that eliminates or reduces the need for in-orbit assembly. An approach at odds with the space IKEA philosophy used to assemble the ISS in-orbit.

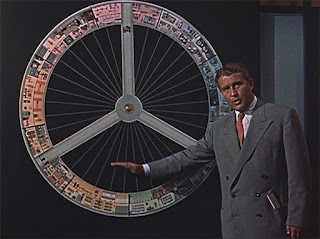

The first unitised station idea explored inflating large tyre tubes (obviously made by Goodyear!) into wheel-shaped space stations — this is what James Webb, the then NASA Administrator, is standing under in the opening image of this essay; the image below shows engineers walking within this tube.

Made from soft materials, like rubber and nylon, there were concerns that collisions with micrometeorites could puncture the station with fatal outcomes. So, a six-month contract was awarded in 1961 to North American Aviation to look into hexagonal space stations, one of Rene Berglund’s many station concepts, made from six hinge-connected rigid pipes. A 15-foot prototype of this system was developed, based on the table-top concept shown below.

This design also folded neatly into a rocket for launch to later deploy in-orbit automatically; the rigidity of its habitable elements also ensured better protection to micrometeorite collisions than Goodyear’s rubber donut. Further, another three inflatable pipes connected the rigid peripheral habitats to a central hub via air-lock doors, which could be sealed in case of rupture. Loftin’s Langley team estimated that either system could be realised for $100 million (approximately a billion dollars in 2025) but, over time, the hexagonal station emerged as the most promising concept in Langley’s Manned Space Laboratory Research Group.

Space station R&D was one of the more active areas at Langley as NASA was unclear about the appropriate path to the moon and an orbiting station seemed like an appropriate precursor to crewed lunar and solar system exploration. Apollo would change everything — in May 1961, President Kennedy’s landmark speech committed America to a lunar landing instead of the original plan to merely orbit the moon.

The Apollo Applications Program: A Pivot Point

The Langley team’s grand vision for artificial gravity space stations was systematically sidelined by Apollo program priorities, budget constraints, and shifting administrative focus (especially post-Apollo). This transformation represents a critical inflection point in space development: a move from ambitious long-term planning to pragmatic incrementalism that continues to shape space exploration today.

The early 1960s marked a dramatic pivot away from NASA Langley’s methodical approach of developing von Braun wheels as lunar mission staging points. Instead, NASA adopted more direct paths to the Moon under Apollo’s mandate. By 1963, the grand rotating hexagon designed for 36 crew members was replaced by the more modest Manned Orbiting Research Laboratory program — a zero-gravity facility for a crew of four focused on conducting basic biomedical and engineering experiments. Like its predecessors, this program was also threatened by cuts but survived into 1965 only through Langley leadership’s persistent lobbying — which positioned larger stations as “the next logical step” after Apollo — to eventually become part of George Mueller’s Saturn-Apollo Applications Program Office.

Mueller, who was NASA’s Associate Administrator and head of the Office of Manned Space Flight, was not just a champion of space stations but also a shrewd leader. With a background in military missile testing, he had accelerated the development of the ‘Saturn V’ with the ‘all-up testing’ method. This led to Apollo 8’s success well ahead of schedule.

But this created a problem of layoffs in von Braun’s rocket team at Marshall Space Flight Center sooner than expected. Apollo Applications was one way of addressing this problem while simultaneously preempting post-Apollo planning hurdles. As part of this program, the teams at Marshall and Langley produced multiple new station concepts including a potential platform for crewed Mars missions and specialised Earth-orbiting stations for astronomy and meteorology. But this work would be short lived as Mueller’s hope for over $1.5 billion in funding for Apollo Applications by 1968 was rebuffed by NASA Headquarters and the Bureau of Budget. He ultimately received only $300 million (equivalent to approximately $2.7 billion in 2025), which effectively eliminated the possibility of ambitious post-Apollo missions.

The competition for Saturn V rockets further limited station development. NASA Administrator James Webb, having fought to secure funding for 15 Saturn V vehicles to accomplish Apollo’s goals, was initially unwilling to allocate any for space station deployment. Only after Apollo 8’s unexpected early success did the possibility emerge of sparing a Saturn V for non-Apollo reasons. So, ambitious ideas for 75-100 person rotating wheel stations, called the Space Base, again briefly sprouted.

Eventually Skylab — America’s first space station — would launch in 1973 on the last ever Saturn V launch. It fell far short of the grand rotating wheel stations previously envisioned and utilized only a fraction of the Saturn V’s lifting capacity. It was an embodiment of the shrinking visions to come.

Post-Apollo, NASA dropped the parallelised program strategy instead adopting an incremental approach to space development. As a result, the Space Shuttle became the ‘logical successor’ and parallel pursuits of ambitious space station programs were abandoned. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union, having shifted focus from lunar landings, launched their Salyut program followed by Mir—conceptually similar to NASA’s scaled-down Manned Orbiting Research Laboratory rather than the ambitious rotating stations.

The early visions of large crews living in rotating structures with artificial gravity now appear as relics relegated to a more optimistic era—one where space architecture was designed for repeatability and scale that could have yielded greater scientific output while answering fundamental questions about artificial gravity’s effects on human health that remain unstudied to this day.

So will I ever get my von Braun Wheel?

Possibly.

The commercial potential for crewed rotating space stations is gaining attention once again. Vast is one of the fast-moving companies aiming to build one. Its founder, Jed McCaleb, echoes von Braun that artificial gravity stations would be useful for Mars transport as they’d be ‘much nicer to live in than inside Starship’ and sees it as essential for humans living in space beyond a year. This is crucial as Starship’s Mars round-trips could be a couple years depending on the orbital positions of both planets; even a one-way journey could edge over a year as we currently lack a crystal clear picture of how the first landings will play out.

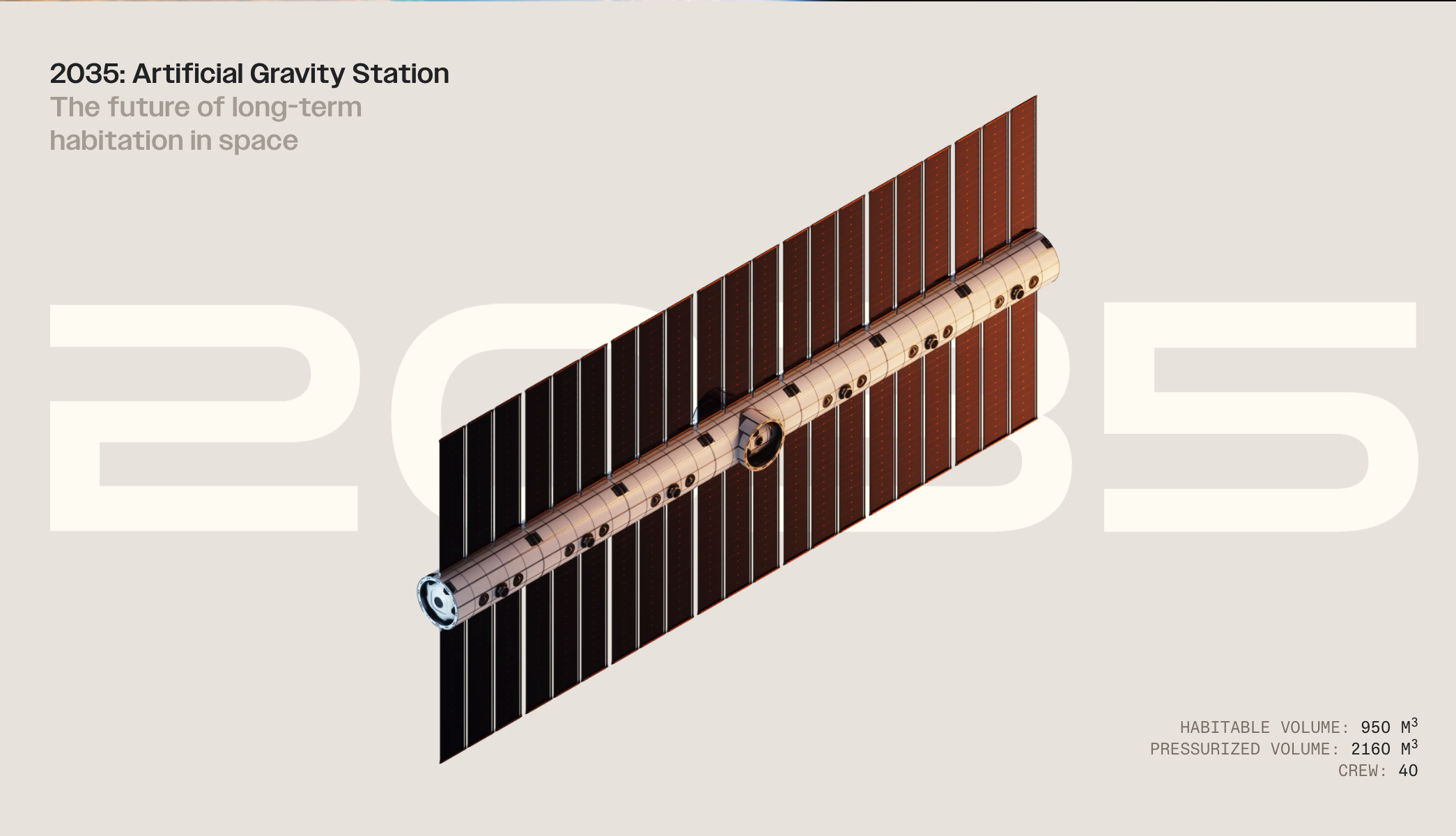

Vast are currently developing smaller zero-gravity Haven stations but their 2035 plan is for a 40-person artificial gravity station. Shaped like a long stick, it spins about its center like a two-bladed fan to produce a range of gravity along its length. The limiting feature of their design is that the most desired higher gravity will only be at the very ends of the stick — this is unlikely to allow its entire crew to enjoy gravity’s perks at all times as doing so will need to cram the entire crew into the stick’s ends. In part, this is because their stations rely on the post-Apollo approach of sending the space station up bit by bit as rigid modules.

The limitations of its modularity are further exemplified if we compare an astronaut’s comfort in Vast’s planned station against other flown modular stations and other concepts. The figure below illustrates that Vast’s planned station will be less comfortable than the ISS per astronaut while also falling short of the von Braun wheel and Space Base concepts from the 60s; these calculations are based on their crew size and habitable volume data that is publicly available.

While volume serves as a useful metric for evaluating comfort in zero-gravity stations where astronauts utilise all three dimensions equally, this measurement becomes less relevant for artificial gravity stations. Once rotation creates a gravitational force, the ‘up-down’ dimension functions more like it does on Earth, making floor area per astronaut the more meaningful measurement — just as we use square footage rather than cubic volume to assess terrestrial living spaces. But determining this is currently hard as it requires much clearer “floor plans” of the interiors of a space station- and these are in scant supply (or at least not publicly available).

That said, space station manufacturers are right to focus on creating larger volumes as they are upstream of areas large enough for even bigger crews to live and work in. Hence the battle to pack larger volumes as compactly as possible into a rocket. This also makes it imperative to develop inflatable space stations to overcome the limitations of rigid ones. The difference is like carrying a packed tent in a backpack versus trying to fit a prefabricated home into a backpack — the former is more mass and volume efficient whereas the latter is going to require either a bigger backpack or many smaller ones. Compared to backpacks, rockets are far more expensive, financially and environmentally, so reducing the number of launches is of paramount importance.

This captures the ingenuity of the Langley team’s counterintuitive idea to stuff an inflatable tyre into a rocket but it was also one ahead of its time. Without advanced high strength fabrics to ensure astronauts’ safety, the rigid hexagonal station was always going to be the victor, even if it packed less efficiently. 50 years hence, we are finally making headway to dispel as myths the earlier concerns about safety of fabric-based stations. The Bigelow Expandable Module (BEAM), a small inflatable module, was added to the ISS in 2016 based on an earlier NASA technology development program, TransHAB, from the 1990s. BEAM is made from high strength fabrics, like Vectran, and has proven stronger to colliding micrometeorites and orbital debris than the other metallic modules of the ISS. Bigelow had also claimed the module offered superior protection from radiation and thermal management.

But, at 16 m³, new efforts are needed into discovering and developing novel high-strength soft materials to enable a 6000 m³ von Braun wheel. Now would be a good time to explore creating the larger Langley/Goodyear-inspired designs not only for artificial gravity stations but also for use in zero-gravity.

The US government wants NASA to put humans on Mars, giving private space companies a business case for large crewed stations that offer better rides to Starship-sized crews. Almost all space station companies also believe they offer platforms for in-space manufacturing to startups like Varda and Space Forge. These companies believe that the ultra-low gravity just outside the Earth’s atmosphere will produce better pharmaceuticals and semiconductors because microgravity enables unique crystal growth patterns, prevents convection, and eliminates sedimentation — factors that can lead to purer materials and more uniform structures than possible on Earth.

This focus on manufacturing means there is no immediate need for artificial gravity, allowing station manufacturers to first focus on rapidly deploying large unitised volumes for uncrewed factories. Of course, this is subject to parallel advances in autonomous robotics otherwise these stations will be crewed. If the Mars priorities take hold then a large inflated volume — such as the Goodyear tube — could simply be spun up to create gravity for journeys to Mars and beyond. Modular designs like the ISS are not designed for such adaptive use cases.

This deliberate sequencing of priorities — focusing on deployable volume first and artificial gravity later — reflects not just technical pragmatism but economic reality as well. It also has the capacity to better adapt to an inversion in priorities if NASA genuinely focuses on getting humans to Mars before in-space manufacturing achieves scale.

Despite the long-term benefits for human spaceflight, it is completely likely that there is no near-term return on investment for any space station, particularly one with the added complexity of artificial gravity. This is a bitter pill we must swallow and perhaps choose to see developing such capabilities as an opportunity to expand existing industrial capacity to push the frontiers of the possible. That is precisely the legacy of Apollo to its credit; while we haven’t been back to the Moon, the development of the Saturn V was, at that time, unprecedented. More importantly, it proved that man’s reach only exceeds his imagination, not his grasp.

Closing Remarks

I am quite critical of Apollo’s role in killing the rotating space station program, which contrasts with current trends of NASA-bashing while regaling the era of manned moon landings. However, Apollo-era NASA was not too dissimilar from SpaceX — beholden to the singular vision of a leader with an arsenal of insane technical talent capable of executing at speed — which is probably why it succeeded.

While today’s NASA lacks such a visionary leader with a singular focus, it has continued to impress by engineering multiple successful landings on Mars. The early Viking landers to the sophisticated Perseverance rover exemplify the kind of success that other national space agencies can only dream about. The European Space Agency’s Beagle 2 and another joint effort with Russia’s ROSCOSMOS on Schiaparelli both failed to land softly on the Martian surface. Meanwhile, pioneering technologists from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab then drove the development of SpaceX’s reusable rockets.

For the first time since the Saturn rockets, we are on the cusp of having a launcher – Starship – that offers an opportunity to make human civilisation a spacefaring one. There is perhaps no bigger indicator of human flourishing than this. But this needs artificial gravity space stations that weave perfectly into the new tapestry for space exploration being stitched by Starship; this successor to the Saturn V needs space station engineering as ambitious as Langley’s in the 1960s to accompany it. This might be best done with a NASA singularly focused on rapidly building volumes in space than companies with large-scale funding.

It’s not all about engineering but also about loosening prohibitive regulations — such as the International Traffic in Arms Regulations — which ensure only a select few nations can collaborate on widening our species’ presence in Earth orbit and beyond. New organisational models (such as Focused Research Organisations) should also be explored — backed by a combination of government or philanthropists — that have a mandate to focus on developing artificial gravity space station technologies.

So, let’s get back to building rotating wheel space stations again.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Ben Southwood and Eli Dourado for reading early drafts of this and providing feedback. All errors are my own.

Further Reading

- Inflatocookbook h/t Tom Milton

- NASA’s Space Settlements Study from the 1970s; the infamous Stanford Torus study.

- James Hansens’s “Spaceflight revolution: NASA Langley Research Center from Sputnik to Apollo”

- T A Heppenheimer’s “Space Shuttle Decision”.

- Matt Novak’s piece for the Smithsonian, Wernher von Braun’s Martian Chronicles

- New Atlas piece with hi-res image at the end of this article of von Braun and Disney.

- Kelly and Zach Weinersmith’s “A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through?”

- Robert Zubrin on Why We Should Settle Mars

- Casey Handmer on Are modular space stations cost effective

- Brian Potter on Building Apollo

- Gary H. Kitmacher’s paper Design of the Space Station Habitable Modules at the 53rd IAC.

- Basic QnA.