On Submitting Your Research to a Journal

Background

I am typically loath to offer general advice (e.g., how to wake up early) and, fortunately for others, it doesn’t happen too often. Instead, I prefer offering specific advice that is actionable (e.g., here is a basic checklist to get X done). Offering advice on the latter requires process knowledge, something I have become good at because I remain embroiled in bureaucraciesVoluntarily by virtue of my job as an academic but also involuntarily by virtue of country of birth. and so have built up a mental corpus of process advice. Though my advice cannot guarantee desired outcomes, it is useful in demystifying what appears to some as opaque systems because they identify as outsiders. Common circumstances where one identifies as an outsider is in getting paperwork done within these bureaucracies mostly because the individual is unfamiliar with the peculiarities of each system. e.g., paperwork for visas, driving licences, university life and other academic-adjacent things.

This post concerns the academic research-related issue of making a journal article submission. An opportunity to write this up has always been around but I hadn’t taken it up; Inkhaven presented another one to advise a researcher who expressed a desire to publish their data-based findings in a peer-reviewed journal. I was very encouraging that they make a submission despite their receiving discouraging guidance from other academics earlier; common push-back has been about their being uncredentialed and not having a co-author with “appropriate” affiliations and other such academic malarkey. While this feedback may eventually turn out to be correct, I think it is worth just doing things to discover the edge of these systems; the bar for publication should be determined by the quality of science and its presentation and especially not by signalling one’s credentialing or the blessing confirmed by co-authorship clout.

So, with the pep talk out of the way, I recommended they make a submission of their write-up to a journal that meets the minimum set of requirements to not get a desk rejection from an editor. I summarised my guidance on how one can go about making such a submission in a Slack message as a high-level guideline; it’s something I have also done for my students back in London but that information is also captured ephemerally in emails and office chat.

Rule of three: if you (or someone else) have explained the same thing 3 times, it is time to write that down. It is clearly interesting enough to keep going back to, and you now have several rough drafts to work with.

Gwern, Inkhaven Slack (November 1, 2025)

I have undoubtedly shared this information more than three times in my life at this point, which makes it worthy of writing up. In fact, as a PhD advisor, it’s pretty silly that I don’t have this guidance handy.

Guidance

The assumption in the following steps is that you have completed some analysis on a topic of interest—potentially even done some literature review—and documented your findings (e.g., on a blog, Google Doc, Jupyter Notebook, etc.).

Step 1. Literature review (again and again and again) to find where to publish your work

Here, I present two approaches to find where to publish your work, with a strong preference for approach 1.

-

Approach 1: Google Scholar is superb for finding scholarly articles. It has a very obvious interface—use it. Most first passes of the research literature are to identify content that is close to the work you have done. What younger researchers looking to get published often miss is in identifying venues that are a good fit for their research. Here are some tips to identify them:

- Under the title of a paper in the G-Scholar search results, you will see green text stating the author name(s) followed by the publication. This is one way to pick a place for submitting your work (after you have read the paper to see that it is in fact relevant to your study, of course!).

- Some authors have profiles on Google Scholar, which also serves as an academic social network—it may be worth clicking on the name of the authors to see what other topics they have published on. Maybe there are other papers relevant to what you are studying; you may find even more journals suitable for your work this way.

.bib file for use with LaTeX. For these reasons, Zotero is called a reference management tool. A browser plugin can also be installed via Zotero that imports papers from Google Scholar to your machine along with all the metadata; link here for Zotero Connector. While not mandatory, it is really worth installing both the primary tooling and the plugin to make your life easier; there’s plenty of tutorials on how to use them that I recommend watching after.

-

Approach 2: Another way to identify a publication venue is by using the Google Scholar’s “Metrics” feature; click on the hamburger on the top left corner to locate that.

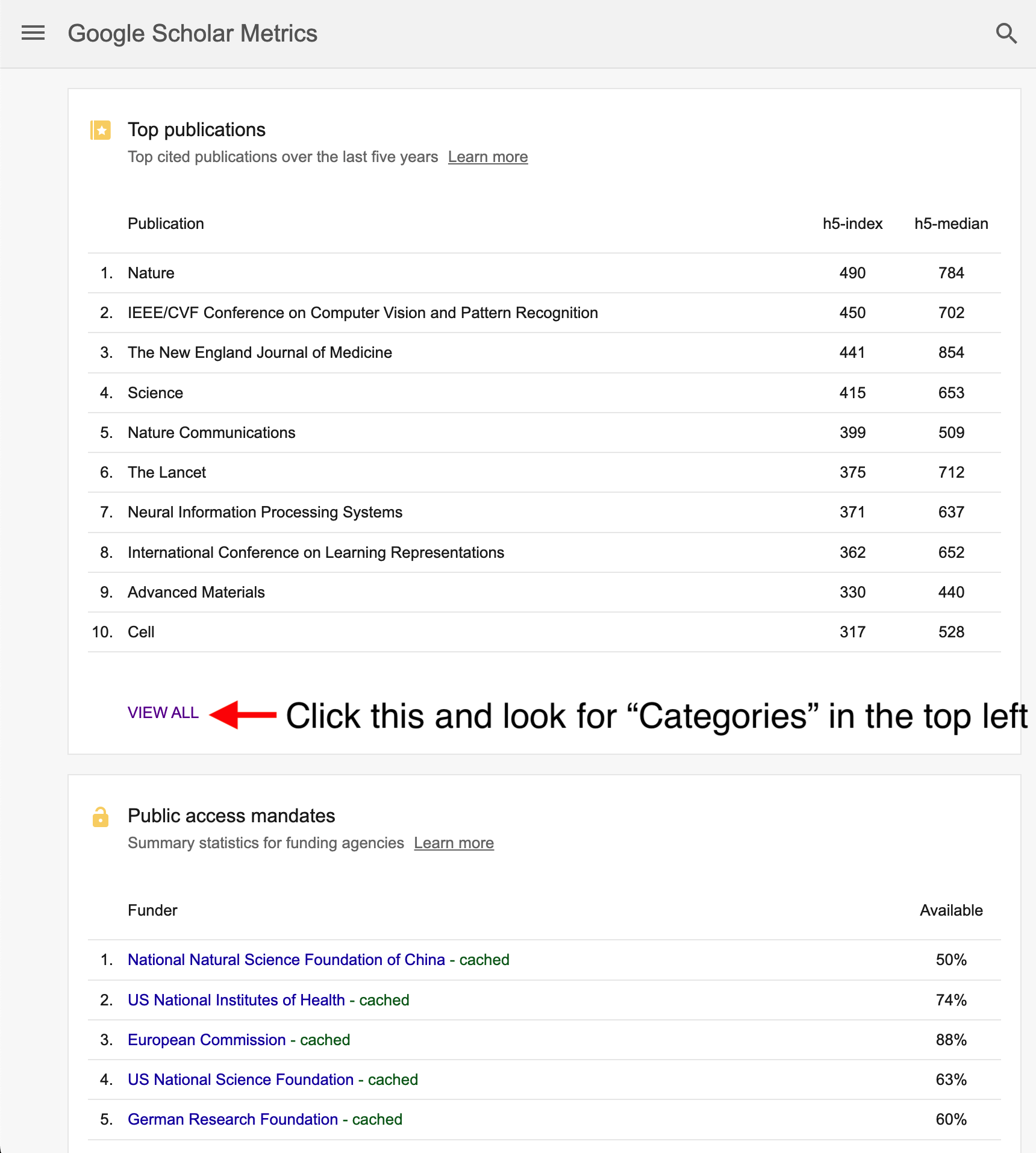

Click the hamburger and find the Metrics option. This reveals a list of top publications, where you should click on “View All”.

Click on View This reveals a long list of a hundred or so scientific publications; you will see the really popular ones (e.g., Nature, Science, etc.) with large numbers against them.

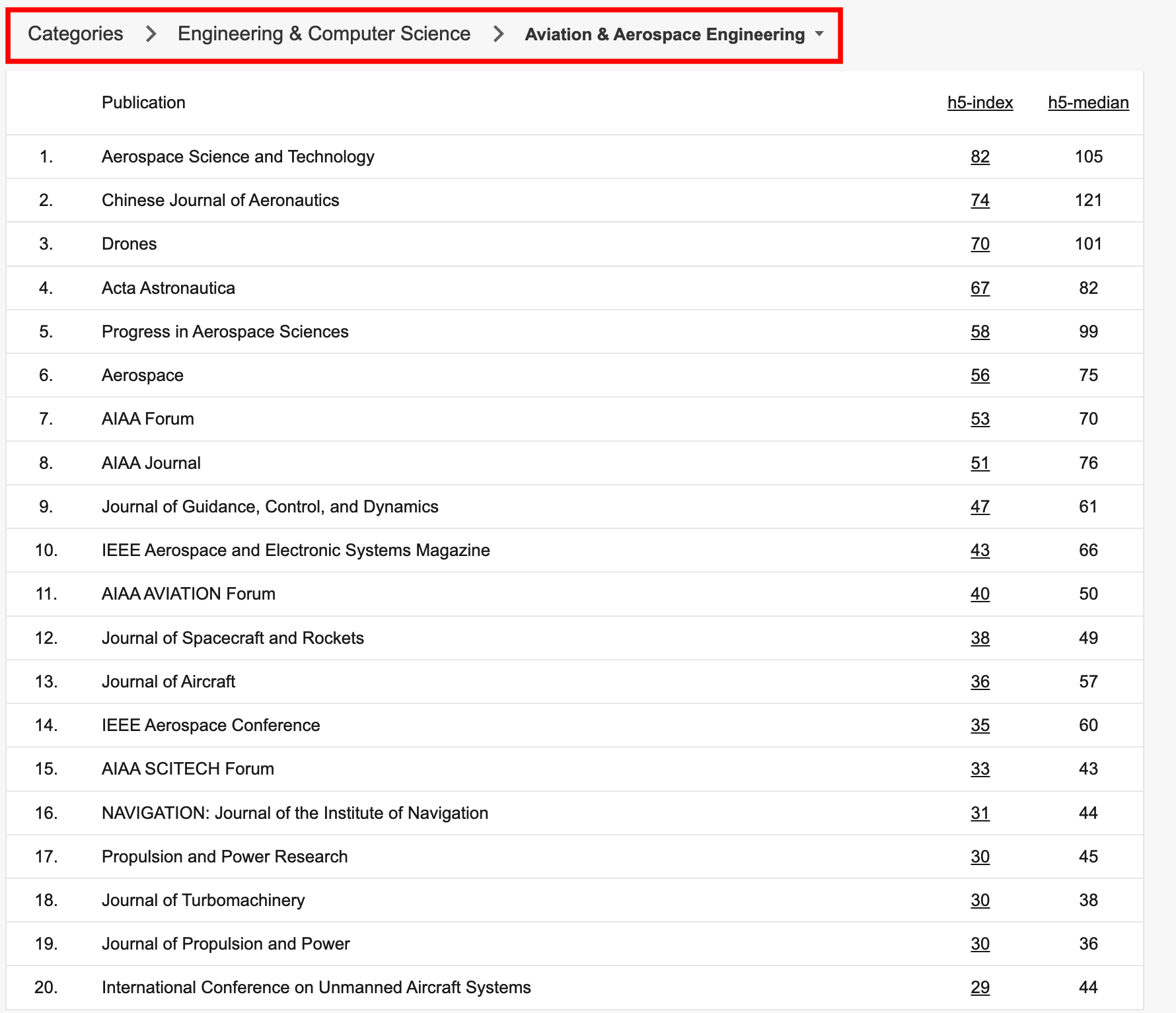

My field, aerospace/spacecraft engineering, is a much smaller niche so doesn’t appear on this list; for most researchers, I suspect this is true so I suggest clicking on the “Categories” button in the left of list of publications and navigate to your specific discipline. In my case, this is what the list looks like.

Category specific list of research publications for aerospace engineering.

Step 2. Document preparation for specific publication

While Step 1 has already helped identify journals that fit the scope of your work, it is still good practice to double-check that your work still fits their scope (these things have a small likelihood of changing). For this post, I will just focus on the aerospace-specific forum American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) that publishes various journals; you can see the scope of their different journals to narrow down which best fits your work.

To find the journal-specific scope and formatting guidelines, again, I recommend Googling the “name of journal author instructions” or some such combination to navigate to instructions on preparing a document that meets specific guidelines. In the case of the AIAA, this is called Journal Author, which is not the most obvious title. This step is, in my opinion, quite certainly the most painful and annoying partI even warned the Inkhaven resident that this part is what will turn them off from the whole idea of making a journal-ready paper. of it all as each journal—not just limited to the AIAA—usually has its own formatting for a paper. Luckily, they often provide templates as a starting point which eases some of the pain—not most of it. Using $\LaTeX$ for document preparation, if that’s an option for the selected journal, definitely makes one’s life easier in the long run1; MS Word templates are also provided but I have never used that to write a paper so I cannot advise anyone on this. Once you have the template, you can spend the next weeks and months drafting your paper!

Step 3. Make a submission!

Once the paper has been drafted and reviewed (many, many times) to iron out all potential issues with its presentation, you are ready to submit. Navigate to the submission portal for the journal and follow the instructions—this is again full of menial chores that are not standardised across journals. Even those from the same publication label i.e., not all Elsevier journals have identical submission portals or requirements.

There is one really important step however that is not obvious to many first-timers:

And with that you are done with making a first submission!

What follows is either:

- a desk rejection by the editor (reasons may go unstated so you go back to Step 1 to determine a different journal); or

- a months-long wait to hear back from reviewers about the decision. The best case decision is that no revisions are requested2. Or you might end up in a rebuttal battle to defend your work if major revisions are requested. Note that rebuttals to reviewers can themselves become many pages longI have once had to write a 10+ page rebuttal—exhausting!. The art of writing a rebuttal is one that I am not going to go into here but is generally about either admitting to the limited scope of work that will be addressed in a future study or serving shit sandwiches (“Yes, that is a great comment from the reviewer and here is why we disagree with it.”).

So with that, you have the instructions on how to make a first submission. Most places are cool with you uploading a preprint to arXivIt’s styled that way because it’s a play on “archive” with the X representing the Greek letter chi. or some other preprint server so I recommend doing that as well. What you cannot do is submit to another venue for peer-review until the decision on this submission is out—while you may think that this is hard to catch, the world is still kinda small.

Rejection is normal3—don’t take it personally but you can navigate a lot of it by ensuring you have high standards for yourself in ensuring the first draft is the best quality it can be. This is not merely about quality of the science but quality of presentation (excellent spelling, grammar, and explanations).

That’s it for this post!

-

I strongly recommend googling why one should prefer using it even if you currently do not know how to use it. I have written up a little document on getting into it via a Jupyter Notebook here. ↩

-

A pleasure I have experienced just once, with a single author publication. This paper is why I believe that academic publication is not all about credentialing and having co-authorship clout. I once just did things! ↩

-

I have been rejected 6-7 times for one of my early papers. Some of these rejections were because I didn’t know that I had to submit cover letters and in other cases because the editor didn’t believe my paper fit with the journal scope. ↩